How did you first come across the subject of cargo cults? What was it about it that fascinated you and led you to explore its history further?

I lived in Papua New Guinea at the end of the eighties and so I guess it originated then. I don't exactly remember when I first heard about them, but I assume they got my interest when I did hear about them because I had some idea of their context, at least geographically. Fundamentally I think much of Melanesian craft is incredibly beautiful and is bound up with the immediate concerns of those cultures so much more inextricably than objects made in the culture I am part of.

In general we are much more isolated from the objects we use – from the materials themselves and the where and the how of manufacture. Many cargo cult activities were a result of World War II and a reaction to the sudden influx of the most alien technology, systems, beliefs and meanings, as well as planes, guns and fridges. What would have been strange and amazing things from completely outside their own context were immediately sublimated into their own cultural beliefs via the appropriation of their form using traditional crafts and materials. I think this shows an amazing ability to adapt and change in order to accept the previously unimaginable. And not least to imbue those objects ("cargo") with meaning relevant to the society in which they suddenly arrived.

We use the phrase "cargo cult" when describing some of these activities, just because it's now an accepted, if very problematic, term. Much of what the invaders saw as "cultish" activities were probably misinterpreted and were in many cases certainly just projections of Western culture's own desires. If we want guns and fridges, they must want guns and fridges too, which is pretty simple and probably wrong on many counts. Applying the blanket term "cargo cult" to a wide-ranging and incredibly diverse set of activities without much in common between different regions is pretty derogatory and ignores the fact that many of these movements were essentially political in nature and stood in opposition to the invaders and their technology rather than in submissive awe of it.

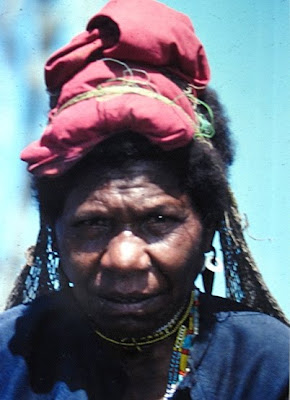

Two images taken during a photography trip in 1988, when Adam was a high school student in Papua New Guinea.

Two images taken during a photography trip in 1988, when Adam was a high school student in Papua New Guinea.What were some of the fun/frustrating parts of constructing the objects for Reverse Cargo? How is it possible to (discreetly?) carry out thousands of IKEA pencils?

I very often have no idea how I am going to make something before I make it. Most of the time my practice involves ideas I'm interested in made whole, rather than a consistent practice of working with particular materials finding its own way to meaning.

I often start with meaning, or at least a seed of it, and then decide how I would like that to take form. As a result, some of it was pretty frustrating! For example I wanted to make a large folded canoe from woven IKEA measuring tape but it always ended up a bit too floppy and I really didn't want to add extra elements like supporting cardboard. Although even that was ultimately fun too, I enjoy that process of exploring a way to do something I haven't done before, even if it fails. Most of it was enjoyable.

The pencils were relatively easy and great fun to work with, although sometimes I think they are almost too perfect. In some ways the more obviously crass colourful consumer crap I used on some of the attachments worked better. But I probably made 8 or 9 trips to IKEA simply for tape and pencils. It's not too hard, I just carried a bag on my shoulder and walked the IKEA maze and every time I passed a pencil holder I'd grab a big handful and put it in my bag. Sometimes I got The Fear (the feeeear!), but then they're free anyway right? And it was fun, hunting and gathering from the IKEA jungle. Inevitably I’d also buy something stupid like a bath mat or a happy plant or a light bulb so I guess if anyone was watching me through secret cameras they didn't care.

Cluster of IKEA pencils attempting to recreate a John Brack painting. This image was taken at Adam's studio when he was working on the show.

Cluster of IKEA pencils attempting to recreate a John Brack painting. This image was taken at Adam's studio when he was working on the show.With Reverse Cargo, do you think you’ve personally exhausted the subject matter of cargo cults, or is this something you’d like to return to soon or in the near future?

I guess so. It wasn't so much specifically cargo cults as subject, but more what I saw as their underlying concerns. It was principally the way you can invest additional meaning beyond the simple market-worth of a particular object or beyond the obvious meaning of its intended use. And the flux of that meaning for those objects once the context is altered. Particularly objects you might feel alienated from and I guess I feel alienated from a lot of contemporary mass consumer culture. So in one way it's ongoing in my work, but I probably won't be using cargo cults as a specific jumping-off point again. These are only my reference points; the work doesn't strictly ‘mean’ these things. Although I personally have internal stuff going on in order to reach the visual conclusions I do, it isn't necessary for the viewer to know that stuff. That's the beautiful thing about art: there is no correct answer. If it's successful for me, it doesn't have to be for you, and more importantly, vice versa.

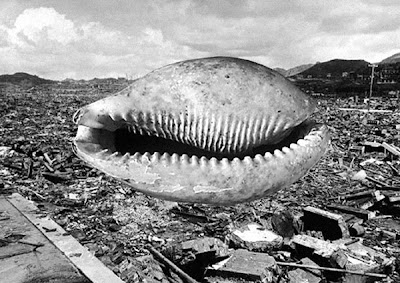

Spread from Adam Cruickshank's limited edition artist book

Recently I went and saw the Art of the Ömie exhibition at the NGV, which is mostly bark paintings from a remote area of Papua New Guinea. The work is really beautiful and even moving, but its context in that gallery really weirded me out and much of the original meaning is not just diluted but completely changed. Most odd was a couple of videos they had playing of the Ömie people painting on a gallery floor. Right in the middle of the wall behind one video of two women working at a large painting on the floor, was this power point. It just struck me as funny and strange and wrong and I couldn't stop looking at that power point. I mean it really transfixed me much more than the work they were doing.

The exhibition also included some totally amazing head-dresses and I couldn't get past the fact that, in their original setting, would you ever be able to see them against a pure white brightly-lit background? It's such a common thing to us, a white background, but originally you could never see them like that. We use white backgrounds for displaying objects because it supposedly lends a void of meaning (a supposedly handy way to read the object unfettered by any connotation), but in this case it had completely and drastically the opposite effect. So I'm thankful for having seen them, but I also feel like I didn't really see them. I don't know if that is all ultimately bad or good, but it's definitely different.

You’ve done some great exhibitions/projects in the past few years. Which one of them was a particular favourite of yours and why?

I'm not really sure I have a favourite. I'm not sure judging art (or craft) hierarchically is very useful. Even though we all do it and it's a massive part of western culture to rate things and put things on a scale of better or worse. Top ten! And I guess it's a common theme in some of my work. Like Western renaissance painting is ranked above traditional Melanesian craft. Those kinds of attitudes are changing, but it's still a common belief. There's this fantastic diagram which I love (stolen from Dexter Sinister) which explains a chronological change in cultural hierarchies really well. But I guess I enjoyed making the Philosopher Kings prints because I find them both hilarious and complex and there's a really nice set of coincidences running through them. I also really enjoyed the work I did for the Repeat Repeat group show at Platform called Enhanced Awareness Campaign. It's not often I am completely satisfied with my own work so it's nice to remember those strange bastard trophies.

Image from Dexter Sinister

Image from Dexter Sinister Friedrich Nietzsche vs Roots Manuva from Philosopher Kings, digital print on cotton rag, 60 x 60cm

Friedrich Nietzsche vs Roots Manuva from Philosopher Kings, digital print on cotton rag, 60 x 60cm

Exotic Blueberry from the Enhanced Awareness Campaign exhibition held at Platform in 2009. Made from trophy parts and $2 shop/supermarket finds.

A few years ago you were working as an art director for a few big companies. Now that you’re freelancing your services, what are looking forward to? On that same note, what would your dream collaboration entail?

Even though a lot of the commercial pay-the-bills work I do is second-hand subject matter for my art practice, I think it's beneficial if the remain as separate as possible. There is a constant antithetical fight between the two and it's often hard for me to resolve that. On one hand I sometimes contribute to mass mainstream culture, a culture that definitely has an explicit and usually a very narrow meaning, while my artwork tries to reject that stuff even while appropriating some of its signals.

But being freelance is much better than working for the man. I guess the best commercial projects to work on are those involving other creative people and organisations who actually interest me and are contributing something positive and who have all their own creative skills and ideas which we can squish together into a gigantic orgy of fun.

Was your decision to use IKEA products arbitrary, or did you have a specific reason for choosing this giant Swedish company?

IKEA is such a great metaphor for right now in western culture. Its largely mass-produced generic objects from a behemoth supermarket headed by one of the richest men in the world, but they do what they can to obscure that. A year or so ago all their in-store signage directly referenced Barbara Kruger. Their advertising is quirky and different. All their objects are ‘designed’ by ‘designers’. And of course they are, it's true, but they even tell you who designed their meat hooks for example. Now I'm pretty sure that particular design has been around for a long time and it wasn't designed by an IKEA designer. What the IKEA designer did, I can only assume, is figure out a cheap way to bend a cheaper material en masse and to ensure that although the pack of 5 only costs $2, they are still make a decent profit, which is more economics than it is design. Don't get me wrong, I love IKEA in many ways. But maybe they should also have in-store photos of someone from their pricing department (wearing architect glasses and a black skivvy). I'm not trying to use IKEA judgementally, although it's easy to read the work that way I guess. It was just such a convenient symbol with such a big range of meanings and connotations when you're talking about the hand crafted.

A photo taken by Adam of an IKEA display featuring Barbara Kruger homage signage.

A photo taken by Adam of an IKEA display featuring Barbara Kruger homage signage.And finally, I’m guessing you’ve already seen this amazing article http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Philip_Movement about how Prince Philip is regarded by the Yaohnanen tribe in Vanuatu as a diving being. What struck me the most is that in 2007, Prince Philip sent the tribe an autographed photo of himself as part of a British TV show called Meet the Natives. What are your thoughts on this and would you be interested in supplying us with a signed headshot of yourself for the winner who correctly guesses how many IKEA pencils were used in IKEA head dress?

A diving being would be great! Prince Philip with a 19th century diving mask, holding a starfish in one hand, a necklace of cowrie shells, a waving wig of seaweed floating behind him. Sorry, I know that was only a typo, but it's a nice image huh?

Yes that was a typo, I meant 'divine being'.

Yeah, I find the whole thing kind of disturbing. I guess a good way to answer your link, is with another link: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/1848553.stm

Prince Philip hasn't previously distinguished himself as the most forward-thinking or culturally sensitive kind of guy. And this particular movement has become such a staple tourist attraction that it's hard to know how much is genuine belief anymore and how much is theatre. And no, I've never seen Meet The Natives, but I just looked it up and I have no idea what to make of it... I'd have to see it. Would you recommend it? Is it on DVD? Can I borrow it off you? And no way are you getting a headshot, sorry, nah.

No comments:

Post a Comment